(This is the latest chapter in a book-in-progress, “Television, and How It Got That Way.” To catch the full book from the start, simply push the category “The Book.”)

As a star student, Kay Smith could have picked almost anything for her Master’s Degree thesis. She chose satellite communication.

It was an odd choice, because … well, there was no satellite communication.

This was 1967, just a decade after Sputnik and just two years after the Early Bird became the first commercial satellite. But Smith felt bigger things were coming.

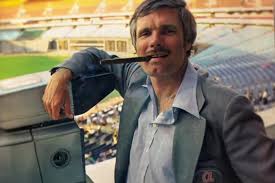

Ten years after that thesis, she created the Madison Square Garden Network. By then, she was Kay Koplovitz; soon, it would be the USA Network; she and Ted Turner (shown here) would pioneer a cable-TV era.

The cable ide had been floating around for decades, but it was just a plan to get better reception. The first attempts were around 1948 in distant parts of Pennsylvania, Arkansas and Oregon.

In ‘50, the first full-scale effort came in rural Pennsylvania: Build a big antenna on a hill and connect it to subscribers’ homes.

The next step – providing extra shows for those subscribers – was far away.

When I was in Fairmont (a Minnesota town near Iowa) in 1970, our cable system offered:

— One station apiece (from Minneapolis or Austin, Minn.) for ABC, CBS, NBC and PBS.

— An independent station from Minneapolis. This allowed us, for instance, to see a guy (dressed as a railroad conductor) show cartoons at noon. An old movie followed at 1.

— And the only made-for-cable contribution – a rotating wheel that showed us a thermometer, a barometer and a wind gauge.

It wasn’t much, but in Minnesota, the weather is sort of important. And a few years later, some mischievous chaps in small-town Michigan came up with an improvement: They snuck into the cable office and put Playboy centerfolds over the rotating weather wheel. Chances are, some little old lady, checking to see if it was a good day to garden, was shocked.

By then, I was in Michigan, witnessing the next step in cable – public access.

That was for anyone. There was Uncle Ernie, who showed his travel films … and Sloucho Barx, who put on a Grouch mask and opined … and, well, me.

Matt Ottinger is a brilliant guy who later got eight consecutive “Jeopardy” answers correct while facing Ken Jennings. (Really.) He wanted to do a show in which we reviewed and discussed movies and TV, sometimes while the camera was panning black-and-white photos.

Viewers could phone in; there was no waiting. The show was, of course, called “Matt and Mike’s Media Meanderings”; it’s hard to resist alliteration.

Some people watched us, for roughly the same reason I once watched a man playing records: It was live and there weren’t a lot of other choices.

Except the alternatives soon emerged.

HBO began with a simple notion. Cable subscribers would pay an extra monthly fee and get Hollywood movies, unedited and uninterrupted.

It was a regional service in 1972 and went national in ‘75. Only later would it turn to what it’s now known for – original, made-for-cable shows.

Some of those arrived gradually – “Fraggle Rock” (a witty Muppets offspring) and “Not Necessarily the News” (a “Daily Show” ancestor) in 1983, “1st & 10” (newcomer Delta Burke as owner of a pro football team) in ‘84, the “Far Pavilions” mini-series in ‘85.

But at first, HBO was known strictly for movies and sports. On its opening night, in ‘72, it showed a hockey game; in 1975, it showed “the thrilla in Manilla,” a boxing epic with Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier.

That was the first TV program sent by satellite. One of the people working on it was Kay Koplovitz … who soon found investors for her own plan, using satellite to propel her network to cable systems.

This began in 1977 as mostly a sports channel, two years before ESPN. As its name (Madison Square Garden Network) suggested, it started with games at the Garden, gradually adding others.

In 1980, it became the USA Network and added more – wrestling, reruns, movies, talk shows, a kid-oriented collection of shorts and more.

Its first comedy (Don Adams in “Check It Out”) was quite awful. A music-video show (“Radio 1990”) had the odd notion of packing in more songs by chopping their length. A better bet was to revive anthologies – Alfred Hitchcock, Ray Bradbury, “The Hitchhiker” –adding occasional new episodes with the old ones.

Much later, USA had an era of excellence. It debuted “La Femme Nikita” in 1997, “Monk” in 2002, “Psych” in 2006, “Burn Notice: in 2007, “White Collar” in 2009, “Suits” (later a hit via reruns on Netflix) in 2011 and the brilliant “Mr. Robot” in 2015.

Koplovitz also launched the Sci Fi Channel (later renamed Syfy, just to be peculiar). It provided a superb “Battlestar Galactica” reboot, plus such gems as “Warehouse 13,” “The Magicians” and “Eureka.”

Syfy also launched one of the truly great shows, “Resident Alien” – which, after three seasons, was sent to USA for 2025.

By then, USA and Sci-Fi had been sold often. Koplovitz was in charge for 21 years, before leaving to become a consultant and run an agency that boosts start-up businesses, particularly ones run by women.

But her main contribution was to show that cable networks could thrive. More proof of that was emerging from Atlanta.

When independent stations had their conventions, we’re told, it was easy to spot Ted Turner.

“Ted would have a blonde on his arm, a couple of drinks in him, and he would deliver a wonderful rant on why he detested news,” Reese Schonfeld wrote in “Me and Ted Against the World” (HarperCollins, 2001).

He has a lot of words and a lot of fun, Schonfeld wrote. “In those days, nobody took Ted seriously.”

But there was a deeply serious side to Turner. He was 19 when his parents divorced, 22 when his younger sister died after a five-year struggle with lupus, 24 when his father committed suicide.

There were more extremes, Schonfeld wrote, for bad or good: “Ted Turner was manic-depressive, although he was not diagnosed until the mid-’80s …. Anyone who’s ever been around a manic-depressive knows that in his manic phase, he had more courage and tenacity than is good for him.”

Except in this case, Turner’s manic gambles paid off.

His father had sold the billboard business, leaving Turner with millions and the prospect of a playboy life. Instead, he bought back the business, prospered and began buying Southern radio stations. In 1969, he sold them and bought a floundering independent TV station in Atlanta.

Like most indies, that had a shaky collection of old comedies, older movies and cartoons. But in ‘72, Turner bought the rights to Atlanta Braves baseball and Atlanta Hawks basketball games.

Four years later, he took two big steps: He bought the Braves and he received federal permission to bounce the station off a satellite to cable systems around the country. On Dec. 17, 1976, WTCH (soon WTBS) went national.

The USA Network arrived nine months later and, Koplovitz pointed out, had one disadvantage: Turner worked it both ways – landing some deals as a local station and others as a national network.

Eventually, that would be worked out; WTBS (now just TBS) can’t deny it’s national. And soon, the cable world would get crowded.

The first arrivals were generally pay-extra channels (HBO in 1972, The Movie Channel in ‘73, Showtime in ‘76) or religious networks. But others were emerging.

In 1977, the Time Warner people (who also had HBO) started an experimental cable system called Qube, in Columbus, Ohio. One portion was “Pinwheel” – simply the same kids’ shorts, in constant rotation.

That led to Nickelodeon, a kids’ network, in 1979 … the year ESPN was born. Many more would follow in the ‘80s.

And in 1982, the Playboy Channel began. It was a step beyond simply taping some centerfold pictures to rotating weather gauges.