As Blacks fought for freedom, two people took opposite approaches.

Harriet Tubman was almost invisible. A tiny person, rarely photographed, she slipped in and out of the South as a spy, a scout and, especially, a master of the underground railroad.

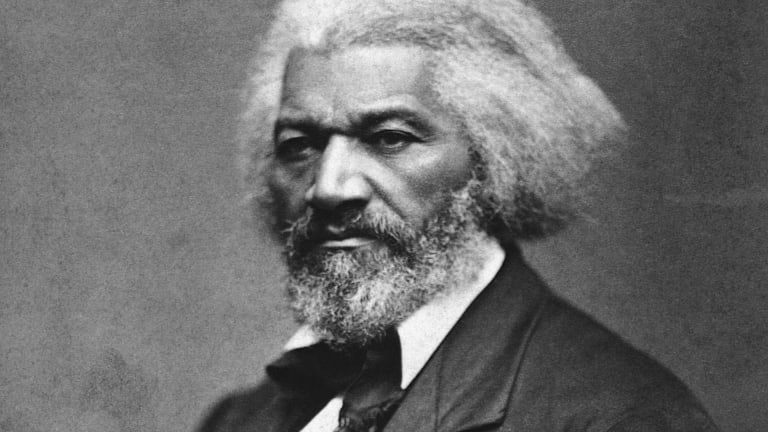

Frederick Douglass (shown here) was the opposite, a man of many words and images. “He wrote so much and he spoke so much and there were so many great speeches,” filmmaker Stanley Nelson said.

Now Nelson – an Oscar-nominee and two-time Emmy-winner – has made films about both people. “Harriet Tubman: Visions of Freedom” and “Becoming Frederick Douglass” will be at 10 p.m. Tuesdays (Oct. 4 and 11, respectively) on PBS and then online. They follow 9 p.m. episodes of Henry Louis Gates’ “Making Black America” — an amiable look at clubs, institutions and traditions, continuing through Oct. 25.

Those film needed different approaches, Nelson told the Television Critics Association. He found “maybe eight to 10 photographs of Harriet Tubman,” mostly in her later years. “Frederick Douglass was the opposite. He’s talked about as the most photographed man of the 19th century.”

And one of the most heard and read. “He wrote so much … and there were so many great speeches.”

That wide-spread attention was important, at a time when some whites thought Africans were lesser people. Here was someone who, in slavery, had secretly mastered his reading skills – even leading a Sunday literary society. He escaped at about 20 and became a preacher, orator and abolitionist.

“There was nothing ordinary about him,” said Farah Jasmine Griffin, an author and Columbia University literature professor. “What I find most compelling is that he never had any self-doubt.”

And Tubman? “I’ve been researching her life for 25 years and I’m still surprised by the things that I find,” said Kate Clifford Larson, a biographer. “She may not have been lettered like Frederick Douglass was … but she, too, was a genius.”

Even as a slave, Larson said, “she was an entrepreneur …. She negotiated with her enslaver to pay him $60 a year and she hired herself out and earned extra money and bought two head of oxen so she could earn even more.”

The plan was to buy her freedom, but that fell apart when the owner died and his widow began selling everyone. At 27, Tubman escaped … then kept risking her freedom to help others. She made at least 13 trips back, guiding at least 70 people North – sometimes all the way to Canada.

While Douglass kept a giant profile, Tubman (sought by bounty-hunters) avoided being noticed.

“She was 5 feet tall, very petite, incredibly strong,” said Nicole London, who co-directed and co-produced both films with Nelson. “She was overlooked. I think she used that to her advantage. Particularly as an enslaved woman, she could find her way to disappear when she needed to.”

And when the war broke out, that skill had a separate use. “Her size allowed her to infiltrate enemy territorty,” London said. “I like to say she was a one-woman SEAL Team 6.”

When the Civil War began, she was 39, Douglass was 44 and both doubled down. He pushed for using Black soldiers, including his sons; she was a spy and a scout, eventually leading a military mission.

After the war, both were active in equality issues for Blacks and women. Douglass died at about 77, Tubman at about 90 (in a home for the aged she co-founded), in worlds they’d helped transform.