Sometime, try to name the old-time movie moguls.

You might come up with the guys who put their names on studios – Disney, Warner, Goldwyn, Mayer. You probably wouldn’t say Darryl Zanuck, who may have topped them all in quantity and quality.

“He wasn’t a one-trick pony,” author/historian Scott Eyman said by phone. “The others found a groove and couldn’t get out of it.”

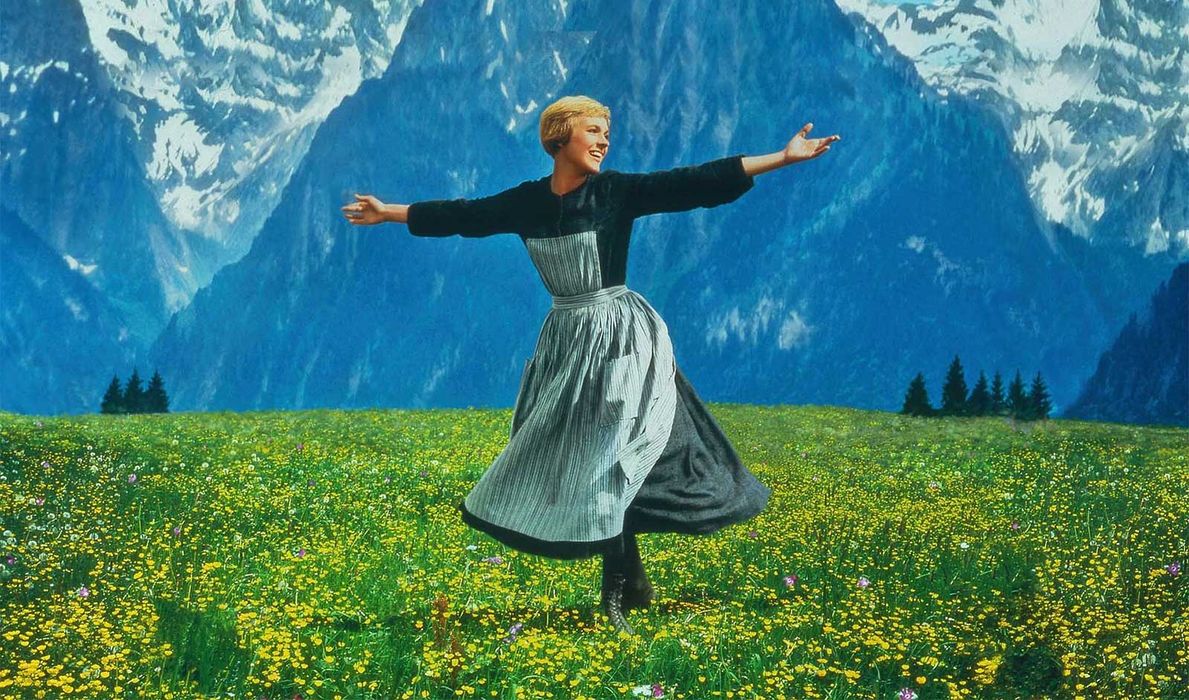

Eyman’s previous 15 books have ranged from John Wayne to Cecil B. DeMille. Now comes “20th Century-Fox: Darryl F. Zanuck and the Creation of the Modern Film Studio” (Running Press). It traces Zanuck from gritty gangster films to the CinemaScope sprawl of “The Robe,” “The Sound of Music” (shown here) and beyond. “He sensed what the public was going to like before the public got there.”

And yes, he had the faults we associate with old movie moguls – ego, temper and sexual affairs. “Today, Zanuck would last about three weeks,” Eyman said.

Family relations were fragile. At one point, his wife voted against him at a stockholders’ meeting; at another, he railed against their son, then replaced him as studio head.

(Richard Zanuck, Eyman said, was actually “smart and calculating. He was a colder customer than his father.” Fired by his dad, he went on to produce “The Sting,” “Jaws,” “Driving Miss Daisy” and more.)

But he also had the key traits of many movie moguls – optimism, idealism, a belief in the American dream and in Hollywood endings.

Most of the others (Disney excepted) were Jewish, fueled by families that overcame hard times in Europe and on the East Coast. Zanuck, an Episcopalian from Wazoo, Neb., might seem out of place.

Still, Eyman said, he felt a kinship. He’d held tough jobs – “a rivet-catcher, for God’s sake”; he’d also savored his maternal grandfather’s stories of success in the old West.

Zanuck sought his own adventures. He lied about his age and joined the National Guard at 15, serving in France during World War I … wrote adventure stories full of purple prose … then, after other jobs, wrote silent movies for Warner Brothers. By 1930, at 28, he was in charge of Warner production.

The gangster movies prospered, but after two years Zanuck and a colleague left, in a pay dispute. They created Twentieth Century Pictures, had a string of hits and then a chance to merge:

Starting with a nickelodeon in New York, William Fox had built a national theater chain and then Fox Film. It was strong on directors, weaker on actors. Its top female was listed as Theda Bara, said to be a leading lady in Paris, Vienna and Berlin; actually, she was Theodosia Goodman of Cincinnati.

In the late ‘20s, sound movies devalued some of Fox’s existing films; then the Depression devalued all of his theaters. He needed to merge into Twentieth Century-Fox.

This seemed like a mismatch, Eyman wrote. Fox Film had theaters, land, a library of films … “but Twentieth Century had Darryl Zanuck and that evened the equation.”

Zanuck could have tried to match his gritty Warner films, “which I still think are magnificent,” Eyman said. But this wasn’t the place. “He realized there’s only one Cagney, only one Edward G. Robinson.”

His Fox movies were strong on character drama, sometimes adding social issues. For his favorites, Zanuck was listed as producer. Three of those – “How Green Was My Valley,” “Gentleman’s Agreement” and “All About Eve” – won best-picture Oscars; 12 others were nominated.

No matter who was listed, however, these were his films. Zanuck ignored the “B pictures,” which were filmed cheaply on another lot, but obsessed on the others, even doing the final editing.

He drifted away from the studio twice: In 1942, he began an active role in World War II; in ‘56. he moved to Europe and, then obsessed on “The Longest Day,” the last of his best-picture nominees.

But he returned in ‘62, when the company seemed to be crumbling. A comedy was shelved (after $2 million) because of Marilyn Monroe’s absences; “Cleopatra” staggered because of Elizabeth Taylor’s absences and more. “What would have driven him crazy was the indecision,” Eyman said. Filming had started and stopped in different locations; the budget kept climbing.

Zanuck put his son in charge of production, and saw new hits, led by “Planet of the Apes,” “MASH,” “Patton,” “Zorba the Greek,” “Butch Cassidy”… and “Sound of Music,” which was promptly followed by a string of failed musicals. “Everyone in Hollywood made that mistake,” Eyman said.

Zanuck needed a scapegoat and fired his son in late 1970… but was soon fired himself.

The company would fade – then soar under Alan Ladd, Jr., with “Star Wars” and more. Its fate went up and down; it was sold to Marvin Davis, then to Rupert Murdoch, then to Disney.

Now Murdoch retains most of the TV business, but Disney owns the movie studio. Renamed “20th Century Studios,” it is one piece of a movie monolith … the sort of place Zanuck would have savored.