There was a time, in the 1960s, when it seemed like everyone wanted to run away and be a rock star.

This was, of course, poor thinking. Some of them should have run away and been rock photographers.

That job had it all, people say in a fascinating new series. Ir was “musical ecstasy” … it was “an hour and a half of sweaty madness” … it stirred “the adrenaline – there’s nothing like it.”

It was a fine job. “I was incredibly lucky,” Gered Mankowitz said via a Zoom interview from England.

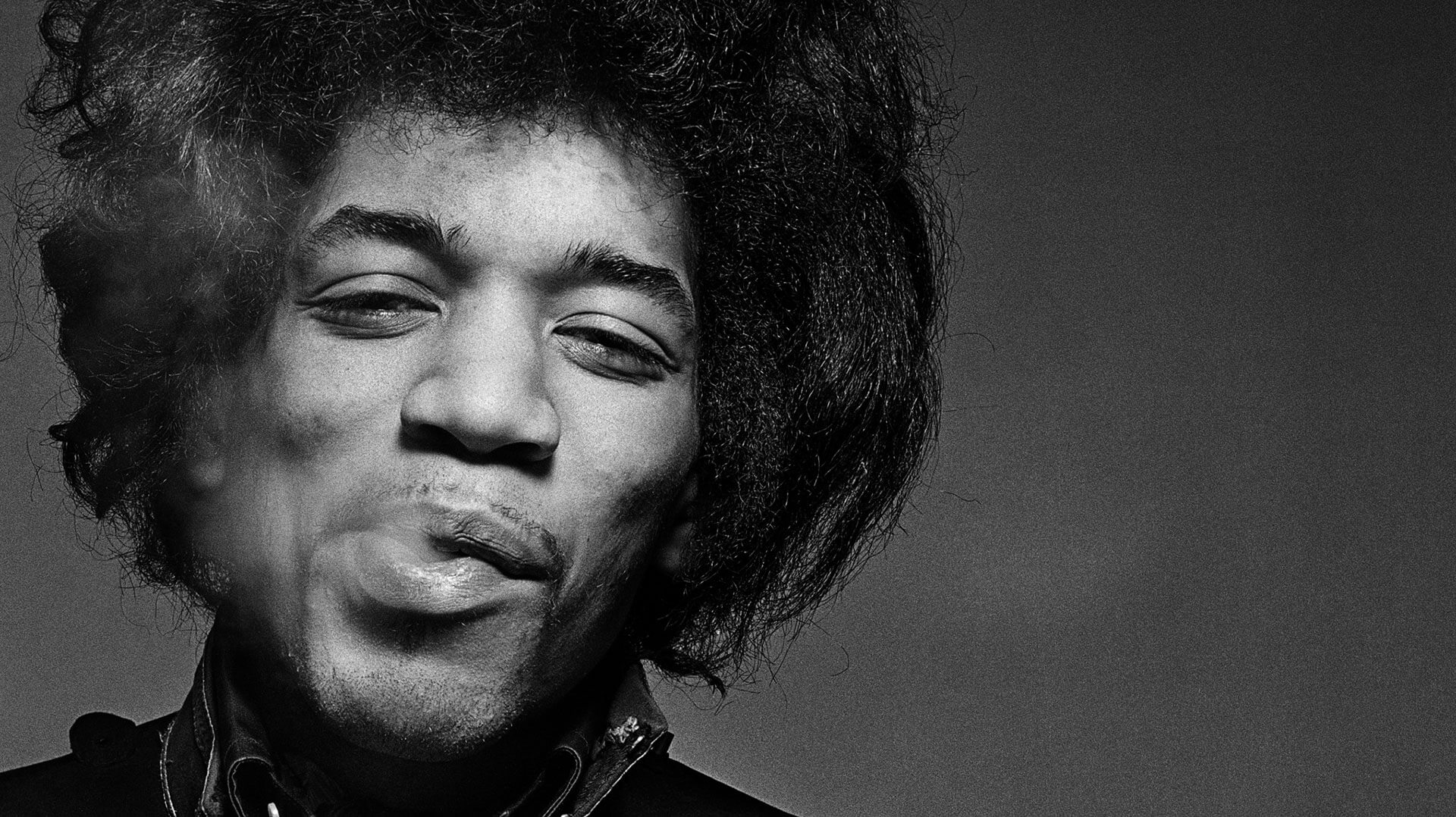

He produced “Icon: Music Through the Lens,” the six-week series that starts at 9 p.m. Friday (July 16) on PBS. He’s also a participant, recalling shooting Jimi Hendrix (shown here) and touring with the Rolling Stones.

Now he’s assembled the memories of many photographers, old and new. When a modern photographer casually said “I told my assistant,” Mankowitz, 74, knew the world had changed. “I didn’t have an assistant,” he said. “The idea of having 30-plus people there, with Puff (Sean Combs) hanging about – that was new, just the scale of it.”

In the old days, the scale in a studio was one-on-one. And one day in 1966, the one was Jimi Hendrix.

Mankowitz hadn’t initially connected with Hendrix’s music, but “I recognized he was a fabulous performer, clearly a brilliant musician.” At first, “I didn’t get it (the music), but I got him.”

Hendrix arrived with hair astray. “He was unkempt, but he threw on these beautiful clothes; he looked fabulous.” Four years later, Hendrix, a superstar at 27, would die of a drug overdose; years after that, Mankowitz’s black-and-white photos would be considered classics.

Others found extremes during studio sessions. Opposite examples, from the “Icon” opener:

– Kurt Cobain arrived four hours late, promptly requesting a vomit pail. As it happens, Jesse Frohman says, the photos turned out well. “He was so stoned, … he was putty in my hands.”

– Madonna, by comparison, was super helpful. Not yet a star, she was just scheduled for a half-hour session in photographer Deborah Feingold’s tiny New York apartment. With no catering budget, Feingold set out some lollipops … which Madonna promptly turned into sexy props.

There were others – Mick Jagger, Hendrix, Bob Dylan, several rappers – who had a great visual sense. “Beyonce is really the nicest, sweetest person,” photographer Albert Watson says in “Icon.”

But many, Mankowitz said, were only into the music, not the visuals. “A lot of my job was holding their hands and trying to guide them to come up with an image.”

It probably shouldn’t surprise us that rock stars vary widely – as do rock photographers.

There was the gonzo approach of Jim Marshall, who shot 500 album covers and died in 2010 at 74. “He was armed and dangerous, with his knife and pistol and cameras,” Mankowitz said. As the official Woodstock photographer, he carried five cameras – two color, three black-and-white – on his neck.

And there’s the gentler approach of others. In “Icon,” Rachael Wright talks about shooting a teen Billie Eilish. “I’m nearly double her age and she’s way cooler than I can ever be.” Like Hendrix, she brought wildly distinctive clothes; unlike him, she needed help getting up, because one outfit was so huge.

Shooting concerts is a different skill, Mankowitz said, requiring anticipation. “If you see it, you’ve missed it.” Of course, he had the advantage of shooting the Stones night after night. He knew exactly when Jagger would gesture, when he would point his butt at the approving crowd.

Mankowitz was only 17 at the time. He dropped out of school at 15, but drew encouragement from his parents – his dad, Wolf Mankowitz, wrote three novels and several movies, getting four British Academy nominations and winning for “The Day the Earth Caught Fire” – and from a mentor.

The mentor shared a photography studio with him, then moved on, leaving a 17-year-old with his own business. The Stones’ first U.S. tour whisked him to a new world, with a limousine at the airport.

The reception was great; the facilities weren’t. “The whole industry of presenting music was immensely amateur-ish then,” Mankowitz said.

At times, wrestling or boxing promoters were in charge, using their usual facilities. “The bands didn’t have their own sound systems then” and the concert venues’ systems were shabby.

So was everything else. “One of the biggest problems for me was that the lighting was so poor.”

He needed to shoot in black-and-white and to improvise. “I was shooting past Mick, into the audience, capturing that feeling.” It was makeshift … and it caught a turning point in music history.