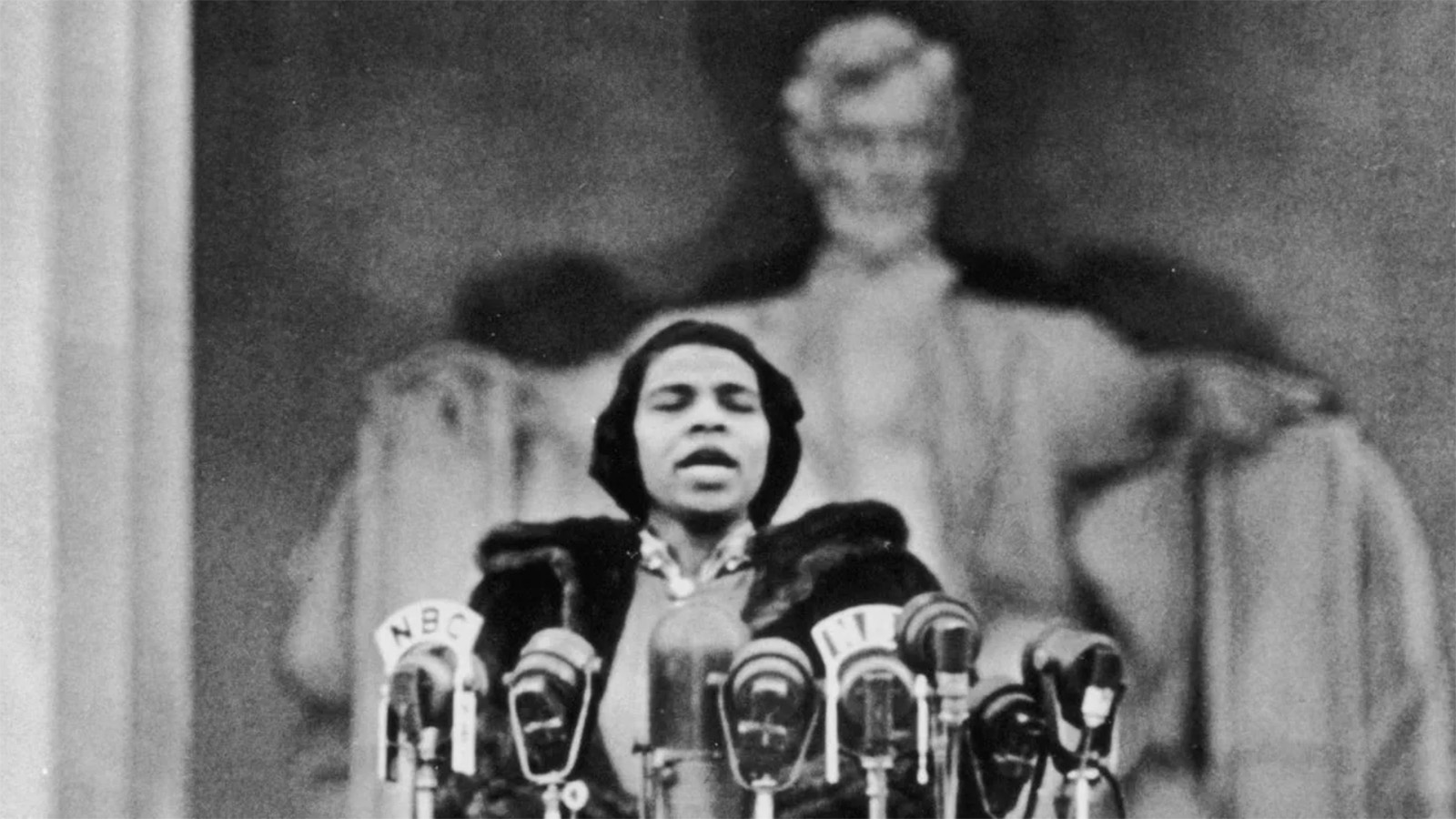

The world seemed to agree that Marian Anderson (shown here) was a great singer.

Audiences cheered; critics raved. Conductor Arturo Toscanani said this was a voice “one is privileged to hear only once in 100 years.”

What people didn’t agree on, in a segregated time, was where she could perform. That’s at the core of “American Experience: Voice of Freedom” (9 p.m. Monday, Feb. 15), a documentary that launches an exceptionally strong week on PBS.

It’s followed on Tuesday and Wednesday by Henry Louis Gates’ resounding “The Black Church: This Is My Story, This Is My Song.” The week ends Sunday with an emotional, Christmastime season-finale of “All Creatures Great and Small.”

Like many of the people in Gates’ film, Anderson first sang in the church. She was 6 when her aunt convinced her to join the Union Baptist choir in Philadelphia; soon, she was doing duets with her aunt and solos, getting paid at local functions.

In 1909, when she was 12, her world changed. Her father died and her family moved in with her grandparents; there was no money for music lessons or for high school.

But friends and neighbors raised money for some lessons and then for the Philadelphia Musical Academy … where she was simply told: “We don’t take colored.”

Instantly, she later recalled, “all of my dreams were just shattered.” But she survived that and an early failure, when an enthusiastic mentor had her singing in a language (German) she hadn’t yet studied.

Anderson bounced back quickly. She won a New York Philharmonic contest at 28, made her Carnegie Hall debut at 31 and toured the world … even performing in 1930s Austria, despite Nazi threats.

At 37, Anderson signed with Sol Hurok, the master impresario. When he heard of Toscanini’s comment, he began billing her as “the voice of the century.”

This was a voice that was in demand, for classical concerts that also included some spirituals. Anderson made $238,000 in1938, the film says, making her the world’s highest-paid singer.

Still, the Daughters of the American Revolution kept its whites-only policy for Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. By a 39-2 vote, it barred her concert.

That led to Anderson’s consummate moment (shown here). On Easter Day of 1939, standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, she gave a free concert to 75,000 people and an NBC radio audience, drawing great praise.

Some 24 years later, Martin Luther King would stand at the same spot, declaring his dream.