History tends to remember a few rebels and reformers.

They’re authors and politicians, mostly. But then there’s the guy – now semi-forgotten – who was once the world’s most famous chemist.

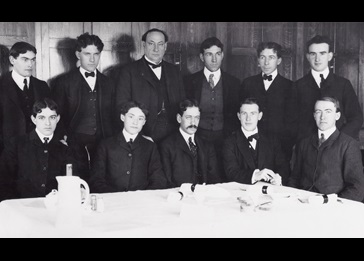

That’s Harvey Wiley (shown here with his young “poison squad”), subject of a fascinating PBS profile Tuesday. He was an early target in the war against science. He was also a reason why we know (sometimes) what we’re eating.

Wiley was born in a log farmhouse in Indiana in 1844, a time when most people were still eating food fresh from the farm. He went to Hanover College (sandwiched around time in the Civil War) and kept studying – a medical degree at Indiana Medical College, an additional bachelor’s from Harvard, time in Germany, where early steps were being made in food science. He taught at Butler and then at Purdue.

The farm-to-table time he had known was drifting away. In a pre-refrigeration world, companies needed new ways to make food seem fresh. Milk was diluted with water, then whitened with chalk or plaster-of-Paris. “Honey” and “maple syrup,” at times, were actually corn syrup; “butter” was oleomargarine made from scraps. Additives included borax, copper sulfate and formaldehyde.

There were no laws to prevent this or to require accurate labels. But in 1882, the U.S. Agriculture Department named him its chief chemist. He was assigned at first to study sorghum, but 20 years later came something bigger: Study the effects of preservatives.

He created “the poison squad”: A dozen healthy young men – getting low pay and free meals — agreed to eat food with increasing amounts of borax, salicylic acid, sodium benzoate and formaldehyde.

None died, but many became ill. It was a key step in illustrating the dangers.

Corporations battled the science and maligned the scientist. Congress resisted, but Wiley had key allies:

There were women. Nationally, they wouldn’t get the vote until 1920, but they formed a strong lobbying force. Fannie Farmer, the influential cookbook writer, was outspoken.

And author Upton Sinclair. After spending two months undercover at a meatpacker, he wrote his 1906 novel “The Jungle.”

And – reluctantly, at first – President Theodore Roosevelt. He was befriended by food executives … but also had memories of rancid canned food issued to his troops in the Spanish American War.

In 1906, Roosevelt endorsed the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act … then took credit for both. They passed and the Bureau of Chemistry was put in charge.

That was Wiley’s department, leading to what became, in 1930, the Food and Drug Administration.

His own tenure was difficult, with attacks from businessmen and politicians. President William Howard Taft nudged him out in 1912.

By then, Wiley had been in government for 30 years and had led the growing department for six. He was 67 – and launched a new career as a columnist and consumer activist for Good Housekeeping.

He would continue until his death at 85. His name or image would be on a stamp, a ship, college buildings and more. He would be famous and controversial … then semi-forgotten … and now the subject of a richly detailed documentary.

– American Experience: The Poison Squad, 9-11 p.m. Tuesday (Jan. 28), PBS

– Based on The Poison Squad, a 2018 book by Deborah Blum, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992 for her Sacramento Bee stories about primate research